On Thanksgiving Saturday, November 26, 1898, the passenger steamship Portland left Boston Harbor with 192 passengers and crew bound for Portland, ME. During the night, New England was hit by a monster storm moving up the Atlantic coast with northeasterly winds gusting to 90 mph, dense snow and temperatures well below freezing. At 5:45 a.m. the morning of November 27, four short blasts on a ship's steam whistle told the keeper of the Race Point Life Saving Station that a vessel was in trouble. Seventeen hours later, life jackets, debris and human bodies washed ashore near the Race Point station, confirming that the Portland had been lost in one of New England's worst maritime disasters. None of the 192 passengers and crew survived this massive storm ... later dubbed "the Portland Gale" after the tragic loss of the ship.

Typical weather patterns in the New England states during late October and November are conducive to the formation of massive storms. At this time of year, large cold air masses from Canada cross the midwestern states on a regular basis. At the same time, the Atlantic Ocean retains its summer heat and these warm waters sometimes spawn hurricanes. When the east-moving cold air masses encounter the warm, humid oceanic air, the result is what New Englanders call Nor'easters: storms that are often severe and often the cause of maritime disasters.

The Gale of 1898 (also called the Portland Gale) began as three air masses: an area of high pressure over the Ohio valley, a weak low-pressure area near Minnesota and another low over the western Gulf of Mexico. By the evening of November 24, the high pressure area and Great Lakes low had both moved eastward. With the counterclockwise (cyclonic) circulation typical of air masses in the northern hemisphere, the Great Lakes low drew in Arctic air from Central Canada, lowering temperatures dramatically across the northern plains. To the south, the Gulf of Mexico low was spreading rain across the southern states from Louisiana to Georgia.

By the morning of November 26, the high pressure area was off the New England coast, the Great Lakes low was centered over Detroit and the southern low was just off the coast of South Carolina. At this point, the two low-pressure air masses were connected by an elongated area of low pressure known as a trough, which facilitated energy exchange between the air masses. As the Great Lakes low continued its eastward advance, the southern low began to move up the east coast, gradually gaining strength and speed. By 3:00 p.m., the southern low had almost completely absorbed the Great Lakes system and was spinning off Norfolk. As the weather system continued to grow, large amounts of moisture absorbed from the Gulf Stream became a massive snowfall that extended from Washington, DC to New York City.

As the storm moved north, a steep pressure gradient developed between the low pressure storm system and the areas of high pressure to the northeast, as well as between the storm system and the Arctic high to the northwest of the storm. The result was unusually strong gales that bettered central and southern New England for the entire day on November 27. By Monday, November 28, the storm had moved off to the northeast, leaving below-freezing temperatures, a devastated coastline and shocked communities that only gradually learned of the Portland's fate.

Reference: Oceanexplorer.noaa.gov

Friday, November 19, 2010

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

Lost or Damaged Vessels

The Portland Gale killed more than 400 people and wrecked more ships than any other storm in the history of New England. It is estimated that over 150 vessels were lost both in harbors and at sea. Many were never heard from after saling. Miles of coastline from Buzzards Bay to Cape Ann were strewn with wreckage.

The physical appearance of the shoreline was altered by the wind and waves. It also changed the course of the North River, separating the Humarock portion of Scituate, MA from the rest of Scituate.

Coastal railroads were damaged in Scituate and Hull. Telegraph and electric lines were severed, interrupting all communications and making it difficult to get news of the Portland to Boston. It was decided to send a wire to France over the trans-Atlantic French cable from the station in Orleans. From there the news was wired back to New York over another cable and then telegraphed to Boston.

Vessels Lost or Damaged in the Portland Gale

NAME OF VESSEL (TYPE), LIFE-SAVING STATION / HOMEPORT / CAPTAIN/CREW / NATURE OF CASUALTY

The physical appearance of the shoreline was altered by the wind and waves. It also changed the course of the North River, separating the Humarock portion of Scituate, MA from the rest of Scituate.

Coastal railroads were damaged in Scituate and Hull. Telegraph and electric lines were severed, interrupting all communications and making it difficult to get news of the Portland to Boston. It was decided to send a wire to France over the trans-Atlantic French cable from the station in Orleans. From there the news was wired back to New York over another cable and then telegraphed to Boston.

Vessels Lost or Damaged in the Portland Gale

NAME OF VESSEL (TYPE), LIFE-SAVING STATION / HOMEPORT / CAPTAIN/CREW / NATURE OF CASUALTY

- A.B. Nickerson (whaling schooner), Cape Cod

- A.B. Nickerson (steamer), Cape Cod

- Abby K. Bentley (schooner), Vineyard Sound / Providence, RI

- Abel E. Babcock (schooner), Boston Bay / Capt. Abel E. Babcock/8 ~ Sometime during the evening of November 26-27 she came to anchor in an exceedingly dangerous place, made unavoidable to circumstances, and dragged onto Toddy Rocks nearly 1 mile from shore, NW of Hull, MA. She was pounded to fragments and all on board perished.

- Addie E. Snow, Cape Cod

- Addie Sawyer (schooner), Vineyard Sound / Calaise, ME

- Adelaide T. Hither (sloop), Plain, NY ~ Blown well up on the beach in Fort Pond Bay. Master requested assistance from keeper to float her, and station crew went over and locked her up ready for launching.

- Africa, Portland, ME

- Agnes, Cape Cod

- Agnes May, Cape Ann

- Agnes Smith, Pt. Judith, RI

- Albert H. Harding (schooner), Boston Bay / Boston, MA

- Albert L. Butler (schooner), Peaked Hill Bars, MA / Boston, MA / Frank A. Leland/7 ~ Two crewmen and one passenger were lost on November 27 when she wrecked high onto a beach near the Peaked Hill Bars Station.

- Alida (schooner), White Head, ME ~ While lying in Islesboro, gale sprang up, parting her anchor chains and driving her to sea. Blown along for some 20 miles, finally fetching up on the flats at Lobster Cove. Crew reached shore without difficulty.

- Aloha (schooner), New Shoreham, RI

- Amelia G. Ireland (schooner), Gay Head, MA / NY NY / Capt. Oscar A. Knapp ~ After she stranded in Menemsha Bight, her crew tried to lower her boat, but it was carried away leaving them without means of escape. They also tried to float a line ashore. The only life lost was a mate who perished in the rigging.

- Anna Pitcher (schooner), New Shoreham, RI / Newport, RI

- Anna W. Barker (schooner), White Head, ME / Sedgwick, ME ~ Wrecked on Southern Island, 3 miles from station. Crew escaped without injury.

- Annie Lee, Cape Ann

- Arabell (schooner), Block Island, RI / Newport, RI

- B.R. Woodside (schooner), Boston Bay / Bath, ME

- Barge (unknown), Boston Bay

- Barge (unknown), Boston Bay

- Barge (unknown), Boston Bay

- Barge (unknown), Boston Bay

- Barge (unknown), Boston Bay

- Barge (unknown), Cape Ann

- Beaver (sloop), Vineyard Sound / Wilmington, DE

- Bertha A. Gross, Cape Ann

- Bertha E. Glover (schooner), Vineyard Sound / Rockland, ME

- Brunhilde (sloop), Point of Woods, NY

- Byssus, Vineyard Sound

- C.A. White (schooner), Boston Bay / Fall River, MA

- C.B. Kennard, Boston Bay

- Calvin F. Baker (schooner), Point Allerton, MA / Dennis, MA / 8 ~ About 3:00 a.m. on November 27, in the midst of the storm with some of her sails blown away, she stranded on the northerly side of Little Brewster Island. She pounded in and fetched up about 75 yards from the rocks. All hands were driven to the rigging as the breakers swept over the ship. The schooner became a total wreck and three men were lost.

- Canaria, Vineyard Sound

- Carita, Vineyard Sound

- Carrie C. Miles, Portland, ME

- Carrie L. Payson (schooner), Chatham, MA ~ Stranded 1 mile N. of the station.

- Cassina, New Shoreham, RI

- Cathie C. Berry (schooner), Vineyard Sound / Eastport, ME

- Champion (brig), Quoddy Head, ME / 6 ~ Wrecked near the Quoddy Head station, but her crew succeeded in reaching shore in their own boat.

- Charles E. Raymond (schooner), Vineyard Sound / Dennis, MA

- Charles E. Schmidt (schooner), Cape Ann / Bridgeton, NJ

- Charles J. Willard (schooner), Quoddy Head, ME / Portland, ME ~ While lying at anchor in West Quoddy Bay, a gale sprang up and her chains parted. She soon stranded and her crew was helped by life-savers and local fishermen.

- Chilion, Cape Ann (schooner) / Portsmouth, NH

- Chiswick, Boston Bay

- Clara Leavitt (schooner), Gay Head, MA / Portland, ME / 7 ~ Stranded the morning of November 27 and didn't last an hour. Breakers swept over her heavily as the crew took to the rigging. Her deck house was destroyed in 20 minutes and all three masts fell when the weather shrouds slackened. Six lives were lost.

- Clara Sayward, Cape Cod

- Clara P. Sewall, Boston Bay

- Coal Barge No. 1, Point Allerton, RI / 5 ~ Wrecked near Toddy Rocks. A line was fired across the vessel, but the crew was too nearly exhausted to be able to do anything with it. The vessel was rapidly breaking up as the life savers fastened lines around their bodies and waded out into the surf to rescue them. All were so chilled that they had to be carried to a nearby house.

- Coal Barge No. 4, Point Allerton, MA / Baltimore, MD / 5 ~ Struck on Toddy Rocks between 12-1:00 a.m. November 27 and went to pieces so quickly that assistance would have been impossible. Of the 5 on board, only the captain and one sailor managed to reach the shore alive by clinging to a piece of the deck house.

- Columbia (pilot schooner), Scituate, MA / 5 ~ She was sighted near Boston Lightship around dusk, lying becalmed. Then the storm struck, and she apparently put about in an attempt to get offshore to ride out the storm. This attempt failed and she had no choice but to anchor. Both anchor chains parted, and she broke up on Cedar Point. Her entire crew was lost and only three bodies were recovered.

- Consolidated Coal Barge No. 1, Boston Bay

- Daniel L.Tenney, Boston Bay

- David Boone, Cape Cod

- David Faust (schooner), Nantucket / Ellsworth, ME

- Delaware, Boston Bay

- D.T. Pachin (schooner), Cape Ann / Castine, ME

- E.G. Willard (schooner), Vineyard Sound/ Rockland, ME

- E.J. Hamilton (schooner), Vineyard Sound / NY NY

- Earl (cat), Cuttyhunk, MA

- Edith (cat), Cuttyhunk, MA

- Edgar S. Foster (schooner), Brant Rock, MA / 8 ~ Wrecked near Brant Rock. Crew succeeded in reaching shore unaided and went to a vacant cottage.

- Edith McIntire, Vineyard Sound

- Edna & Etta (schooner), Great Egg, NJ / Somers Point, NJ ~ Stranded on the meadows during the storm. Master asked for help from the station and the crew boarded the vessel. At high water they put rollers under her and hove her afloat.

- Edward H. Smeed (schooner), New Shoreham, RI

- Ella F. Crowell, Boston Bay

- Ella Frances (schooner), Cape Cod / Rockland, ME

- Ellen Jones, Cape Cod

- Ellis P. Rogers (schooner), Cape Ann / Bath, ME

- Elmer Randall, Boston Bay

- Emma, Boston Bay

- Ethel F. Merriam (schooner), Cape Cod / Booth Bay, ME

- Evelyn, Cape Ann

- F.H. Smith (schooner), Cape Cod / New Haven, ME

- F.R. Walker (schooner), Cape Cod / Gloucester, MA

- Fairfax (steamer), Cuttyhunk, MA ~ During the gale and snowstorm, she brought up on the Bow and Pigs ledge, about 3 miles to the W. of the station but was not immediately discovered by the patrol on account of thick weather. Her master stated crew and passengers didn't wish to leave until they could be transferred to a tug. After dinner, a tug being seen on the way to the stranded vessel, surfmen close-reefed sail and stood down to lend a hand in assisting with the transfer of passengers, crew and baggage to the tug which then proceeded to New Bedford.

- Falcon, Vineyard Sound

- Fannie Hall, Portsmouth, NH

- Fannie May, Rockland, ME

- Flying Cloud, Cape Ann

- Forest Maid (schooner), Portsmouth, NH / Portland, ME

- Fred A. Emerson (downeast lumberman), Boston Bay

- Friend (steamer), Cuttyhunk, MA / Boston, MA

- Fritz Oaks, Boston Bay

- G.M. Hopkins (schooner), Boston Bay / Provincetown, MA

- G.W. Danielson (steamer), New Shoreham, RI

- Gatherer, Cape Ann

- George A. Chaffee, Cape Ann

- George H. Miles, Vineyard Sound

- Georgietta (schooner), White Head, ME ~ Stranded on Spruce Head Island during the heavy gale and snowstorm. In attempting to haul her off, the foremast and main topmast were carried away.

- Grace (schooner), Cape Cod / Ellsworth, ME

- Gracie, Cape Cod

- Hattie A. Butler (schooner), Vineyard Sound / Hartford, CT

- Henry R. Tilton (schooner), Point Allerton, MA / 8 ~ Parted chains during the hurricane and stranded near the station. All members of the crew landed without accident. The sea was very heavy and at times washed over the sea wall, submerging the surfmen and their apparatus.

- Ida, Boston Bay

- Ida G. Broere (cat), Lone Hill, NY / Patchogue, NY ~ Parted moorings during the gale and went ashore 1/2 mil from the station on the bay side. Surfmen could do nothing for her on account of sea and ice until December 4.

- Idella Small (schooner), Davis Neck, MA / Portland, ME / 3 ~ Driven ashore by the gale on the east side of Davis Neck. As she took bottom one of her crew jumped ashore and sought help at the station. Two others on board safely off. On the next high tide after she went ashore, the vessel drifted up on the beach at Bay View and became a total wreck.

- Inez Hatch, Cape Cod

- Institution (launch), Boston Bay

- Ira and Abbie (schooner), Block Island, RI / New London, CT

- Ira Kilburn, Portsmouth, NH

- Isaac Collins (schooner), Cape Cod / Provincetown, MA

- Island City, Vineyard Sound

- Ivy Bell (schooner), Jerrys Point, NH / Damariscotta, ME/ 4 ~ Dragged ashore near the entrance to Portsmouth Harbor. All crewmen taken off safely.

- J.C. Mahoney (schooner), Cape Ann / Baltimore, MD

- J.M. Eaton (schooner), Cape Ann / Gloucester, ME

- James A. Brown (schooner), Vineyard Sound / Thomaston, ME

- James Ponder (schooner), Vineyard Sound / Wilmington, DE

- James Webster, Boston Bay

- John Harvey (barge), Pt. Judith, RI / NY NY

- John J. Hill, Boston Bay

- John S. Ames (schooner), Boston Bay

- Jordon L. Mott (schooner), Wood End, MA / Rockland, ME / Capt. Dyer/5 ~ One life lost when she sank at her anchor in Provincetown Harbor the early morning of November 27. Four men, who were quickly approaching collapse after having been in the shrouds for 15 hours, crept down from the rigging as the life-savers arrived. The lifeless body of the captain's father was lashed in the rigging.

- Juanita ~ This vessel, less than a year old, was blown ashore at Cohasset, MA. Her crew escaped in the dories; all survived.

- King Phillip, Cape Cod

- Knott V. Martin, (schooner) Cape Ann / Marblehead, MA

- Leander V. Beebe (schooner), Boston Bay / Greenport, NY

- Leora M. Thurlow, Vineyard Sound

- Lester A. Lewis (schooner), Wood End, MA / Bangor, ME / 5 ~ Sank in Provincetown Harbor the early morning of November 27. Her crew took refuge in the rigging, where they perished before help could arrive.

- Lexington (schooner), New Shoreham, RI

- Lillian, Portland, ME

- Lizzie Dyas (schooner), Boston Bay

- Lucy A. Nickels (bark), Point Allerton, MA / Searsport, ME / 5 ~ Wrecked by the hurricane on Black Rock. In attempting to swim to the rock, the master and mate was drowned. The other members of the crew found in a gunning hut on the rock. The vessel was a wreck and one of the survivors seriously injured.

- Lucy Bell (schooner), Boston Bay / Patchogue, NY

- Lucy Hammond (schooner), Vineyard Sound / Machias, ME

- Lunet (schooner), Naushon Island, MA / Calais, ME

- Luther Eldridge (schooner), Nantucket / Chatham, MA

- M. and A. Morrison (schooner), Herring Cove, MA

- Marion Draper (schooner), Vineyard Sound / Bath, ME

- Mary Cabral, Cape Cod

- Mary Emerson, Boston Bay

- Mascot (cat), Cuttyhunk, MA / Gloucester, MA

- M. E. Eldridge, Vineyard Sound

- Mertis H. Perry (fishing schooner), Brant Rock, MA / Joshua Pike/14 ~ Dashed ashore 2 mi. NNW of the life-saving station between 9-10:00 a.m. on November 27. 5 men were lost. The conditions of the weather were such that it was impossible for the life-savers to discover the vessel when she came ashore, much less reach her in time to save lives.

- Michael Henry, Cape Cod

- Mildred and Blanche, Cape Cod

- Milo (sloop), Boston Bay / Boston, MA

- Multnoman, Portsmouth, NH

- Nautilus, Cape Cod

- Nellie B. (sloop), New Shoreham, RI

- Nellie Doe (schooner), Vineyard Sound / Bangor, ME

- Nellie M. Slade (bark), Vineyard Sound / New Bedford, MA

- Neptune, Portland, ME

- Neverbuge (cat), Cuttyhunk, MA

- Newburg, Vineyard Sound

- Newell B. Hawes (schooner), Plum Island, MA / Wellfleet, MA / 5 ~ Driven ashore during the gale and snowstorm and fetched up near the lighthouse. Surfmen worked with the schooner's crew until the 4th of December when they succeeded in floating the vessel.

- Ohio (steamer), Spectacle Island

- Papetta, Vineyard Sound

- Pentagoet, Cape Cod

- Percy (schooner), New Shoreham, RI

- Phantom, Boston Bay

- Philomena Manta (schooner), Cape Cod / Provincetown, MA / lost on fishing banks of MA Feb 1905)

- Pluscullom Bonum (schooner), Boston Bay / Boston, MA

- Portland, Off Cape Cod

- Powder vessel (steamer), N. Scituate, MA

- Queen of the West (schooner), Fletcher’s Neck, ME / 2 ~ Wrecked on Fletchers Neck. Both crewmen and a dog brought off safely.

- Quesay, Vineyard Sound

- Rebecca W. Huddell (schooner), Vineyard Sound / Philadelphia, PA

- Reliance (cat), Point of Woods, NY

- Rendo, Portland, ME

- Rienzi (schooner), Cape Ann / Sedgwick, ME

- Ringleader, Portsmouth, NH

- Robert A. Kennier (schooner), Boston Bay / NY NY

- Rose Brothers (schooner), New Shoreham, RI / Newport, RI

- Rosie Cobral, Boston Bay

- S.F. Mayer, Rockland, ME

- Sadie Wilcutt, Vineyard Sound

- Sarah, Cape Ann

- School Girl (schooner), Cape Cod / Provincetown, MA

- Schooner (unknown), Boston Bay

- Schooner (unknown), Boston Bay

- Schooner (unknown), Boston Bay

- Schooner (unknown), Boston Bay

- Schooner (unknown), Cape Cod

- Schooner (unknown), Cape Cod

- Secret (cat), Cuttyhunk, MA

- S. E. Raphine (downeast lumberman), Boston Bay

- Silver Spray, Portland, ME

- Sloop (unknown), Boston Bay

- Sloop (unknown), Boston Bay

- Sloop (unknown), White Head, ME

- Sport (cat), Cuttyhunk, MA / Boston, MA

- Startle (sloop), Boston Bay / NY NY

- Stone Sloop (unknown), Boston Bay

- Stone Sloop (unknown), Boston Bay

- Stranger (cat), New Shoreham, RI

- Sylvester Whalen (schooner), Cape Cod / Boston, MA

- T.W. Cooper (schooner), Portsmouth, NH / Machias, ME

- Tamaqua (ocean tug), Boston Bay

- Thomas B. Reed, Cape Cod

- Two Sisters, Portsmouth, NH

- Two-Forty, Boston Bay

- Union, Boston Bay

- Unique, Cape Cod

- Unknown vessel, Boston Bay

- Valetta, Vineyard Sound

- Valkyrie (sloop), New Shoreham, RI

- Verona (schooner), Boston Bay / Cleveland, OH

- Vigilant, Cape Cod

- Virgin Rock (schooner), Boston Bay / Boston, MA

- Virginia (downeast lumberman), Boston Bay

- W.H. DeWitt, Cape Ann

- W.H.Y. Hackett (Schooner), Portsmouth, NH

- Watchman (downeast lumberman), Boston Bay

- Wild Rose (schooner), Cranberry Isles, ME ~ Stranded and sunk in a terrific gale. Crew safely taken off board.

- William Leggett, Cape Ann

- William M. Wilson (schooner), Wachapreague, VA / 6 ~ Sprung a leak and sank 3 miles NNE of station. Surfmen set out to her assistance by hauling the boat along the beach, it being impossible to pull out to her from the station. They saw the crew from Metomkin Inlet Station sail out to her and take off the crew.

- William Todd, Vineyard Sound

- Wilson and Willard (schooner), Cape Ann / Boston, MA

- Winnie Lawry, Vineyard Sound

- Wooddruff, Northport, ME

|

| Albert Butler |

|

| Henry R. Tilton |

|

| Juanita |

|

| Mertis H. Perry |

|

| Portland |

Monday, October 18, 2010

The Steamer Portland

The steamer Portland was built at Bath, ME in 1889 for the Boston-Portland run and was the pride of the New England coastal steamer fleet. She was strongly built, outfitted with the finest furnishings, and was run by an excellent crew. However, like the other big sidewheel steamers popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s, her long, shallow wooden hull and massive overhanging sponsons (housing her paddlewheels) made her vulnerable to rough seas.

Portland departed Boston for the final time at 7 p.m. on 26 Nov 1898, crowded with passengers returning home after the Thangsgiving holiday. At the time of her departure the weather was worsening, but had not yet deteriorated to the point that sailing was deemed inadvisable. As she steamed northeast towards Portland, however, conditions quickly worsened. At 9:30 p.m. she was sighted passing Thatcher's Island, a short distance northeast of Boston, her progress clearly hampered by the deteriorating weather. Although she was still making headway against the storm at this sighting, she probably did not get far before her progress was stopped.

Between 11 and 11:45 p.m. Portland was sighted three times, but this time to the southeast of Thatcher's Island - she was being driven south by the storm. When sighted at 11:45 p.m., she is said to have shown severe storm damage, especially to the superstructure. By this time conditions on the steamer must have been dreadful, and all aboard must have known they were in grave danger. Unable to make progress against the storm and unable to make for safe port, Portland's only hope lay in working her way offshore and riding out the storm at sea. Her attempts to reach the open sea accounted for her slow movement to the east between the 9:30 and 11:45 sightings.

At 5:45 a.m. the following morning, lifesavers on Cape Cod heard four blasts of a steamer's whistle. It is now believed the whistle was that of the doomed Portland. In the course of the night the storm had driven her even further backwards, so she was now far southeast of Boston. Between 9:00 and 10:30 that morning the eye of the storm passed over, and several persons claim to have seen Portland wallowing five to eight miles offshore, clearly in great peril. No further sightings were made that day, as the storm closed in once again.

At 7:30 that night, more than 24 hours after Portland had sailed, a lifesaver on his regular beach patrol found one of the steamer's lifebelts washed up on the beach. Fifteen minutes later several fourty-quart dairy cans were found in the surf. At 9:30 doors and woodwoork from Portland were found. Around 11:00 the rising tide brought in massive quantities of wreckage, giving clear evidence that Portland had been lost. It is said that this tragic news was communicated to the world via a bizarre relay - by telegraph across the trans-Atlantic cable to France, then to New York via another undersea cable, and from there on to Boston - for the telegraph cables between Cape Cod and Boston had been blown away by the storm.

All those aboard Portland, believed to be a total of 191 passengers and crew (the only passenger list was lost with the ship), were killed. Eventually 36 bodies were recovered along the beaches.

Many of the bodies wore wristwatches that had stopped at 9:15. It is unclear, however, if this indicates the ship was lost at 9:15 a.m., or at 9:15 p.m.. Although there are several reports of the ship being sighted, afloat, between 9 a.m. and 10:30 a.m. that day, the exact times of those sightings are not known. If any of those sightings took place after 9:15 a.m., then the ship must have survived until 9:15 p.m. that day, some 26 hours and 15 minutes after she had started her doomed voyage. However, Portland would not have carried enough fuel to remain at sea, in storm conditions, for over 24 hours. She could have burned furnishings, interior bulkheads, and other wooden materials to keep the boilers running, but the quantity of this material washed ashore tends to indicate this action was not taken.

It is also highly questionable whether she could have held together for 24 hours, given the terrible sea conditions. Still, the fact that major debris did not begin to wash ashore until 9:30 p.m. suggests the Portland had survived into the night - surely, if she had been wrecked at 9:15 a.m., debris would have been washed ashore in the morning. Because the exact time of the final sightings cannot be firmly established, it is impossible to conclusively determine the exact time of Portland's loss - either 9:15 a.m., or 9:15 p.m., on Sunday, 27 Nov 1898.

Portland's remains were eventually located on the seafloor about seven miles offshore, and have since been explored. The small schooner Addie E. Snow was also lost during the storm, and her remains lie less than 1/4 mile from Portland's grave. It is thought that the two vessels may have collided, hastening their ends.

The tragedy of the Portland was deeply felt in the New England seafaring community, and lead to many changes. Most significantly, the adoption of steel-hulled, propeller-driven steamers was greatly hastened, especially on the rugged "outside" or "Down-east" runs. The sidewheel steamers lasted for many more decades, but increasingly on "inside", or protected, runs.

Portland departed Boston for the final time at 7 p.m. on 26 Nov 1898, crowded with passengers returning home after the Thangsgiving holiday. At the time of her departure the weather was worsening, but had not yet deteriorated to the point that sailing was deemed inadvisable. As she steamed northeast towards Portland, however, conditions quickly worsened. At 9:30 p.m. she was sighted passing Thatcher's Island, a short distance northeast of Boston, her progress clearly hampered by the deteriorating weather. Although she was still making headway against the storm at this sighting, she probably did not get far before her progress was stopped.

Between 11 and 11:45 p.m. Portland was sighted three times, but this time to the southeast of Thatcher's Island - she was being driven south by the storm. When sighted at 11:45 p.m., she is said to have shown severe storm damage, especially to the superstructure. By this time conditions on the steamer must have been dreadful, and all aboard must have known they were in grave danger. Unable to make progress against the storm and unable to make for safe port, Portland's only hope lay in working her way offshore and riding out the storm at sea. Her attempts to reach the open sea accounted for her slow movement to the east between the 9:30 and 11:45 sightings.

At 5:45 a.m. the following morning, lifesavers on Cape Cod heard four blasts of a steamer's whistle. It is now believed the whistle was that of the doomed Portland. In the course of the night the storm had driven her even further backwards, so she was now far southeast of Boston. Between 9:00 and 10:30 that morning the eye of the storm passed over, and several persons claim to have seen Portland wallowing five to eight miles offshore, clearly in great peril. No further sightings were made that day, as the storm closed in once again.

At 7:30 that night, more than 24 hours after Portland had sailed, a lifesaver on his regular beach patrol found one of the steamer's lifebelts washed up on the beach. Fifteen minutes later several fourty-quart dairy cans were found in the surf. At 9:30 doors and woodwoork from Portland were found. Around 11:00 the rising tide brought in massive quantities of wreckage, giving clear evidence that Portland had been lost. It is said that this tragic news was communicated to the world via a bizarre relay - by telegraph across the trans-Atlantic cable to France, then to New York via another undersea cable, and from there on to Boston - for the telegraph cables between Cape Cod and Boston had been blown away by the storm.

All those aboard Portland, believed to be a total of 191 passengers and crew (the only passenger list was lost with the ship), were killed. Eventually 36 bodies were recovered along the beaches.

Many of the bodies wore wristwatches that had stopped at 9:15. It is unclear, however, if this indicates the ship was lost at 9:15 a.m., or at 9:15 p.m.. Although there are several reports of the ship being sighted, afloat, between 9 a.m. and 10:30 a.m. that day, the exact times of those sightings are not known. If any of those sightings took place after 9:15 a.m., then the ship must have survived until 9:15 p.m. that day, some 26 hours and 15 minutes after she had started her doomed voyage. However, Portland would not have carried enough fuel to remain at sea, in storm conditions, for over 24 hours. She could have burned furnishings, interior bulkheads, and other wooden materials to keep the boilers running, but the quantity of this material washed ashore tends to indicate this action was not taken.

It is also highly questionable whether she could have held together for 24 hours, given the terrible sea conditions. Still, the fact that major debris did not begin to wash ashore until 9:30 p.m. suggests the Portland had survived into the night - surely, if she had been wrecked at 9:15 a.m., debris would have been washed ashore in the morning. Because the exact time of the final sightings cannot be firmly established, it is impossible to conclusively determine the exact time of Portland's loss - either 9:15 a.m., or 9:15 p.m., on Sunday, 27 Nov 1898.

Portland's remains were eventually located on the seafloor about seven miles offshore, and have since been explored. The small schooner Addie E. Snow was also lost during the storm, and her remains lie less than 1/4 mile from Portland's grave. It is thought that the two vessels may have collided, hastening their ends.

The tragedy of the Portland was deeply felt in the New England seafaring community, and lead to many changes. Most significantly, the adoption of steel-hulled, propeller-driven steamers was greatly hastened, especially on the rugged "outside" or "Down-east" runs. The sidewheel steamers lasted for many more decades, but increasingly on "inside", or protected, runs.

Sunday, September 19, 2010

Steamer Portland's Crew

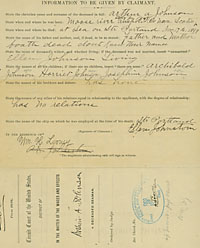

Carrie Harris, a stewardess aboard the Portland, died when the steamer went down in November 1898. Her sister Ellen Johnston filed a claim for Carrie's wages.

Reconstructing the List of the Steamer's Crew

On November 27, 1898, the steamer Portland departed Boston for her scheduled run to Portland, Maine. She was never seen again. That evening a storm arose in the waters off New England. Before it abated the following day, hundreds of vessels and shore properties were damaged. The Portland was lost with no survivors, and that storm has come to be known as "The Portland Gale." To this day it is not known exactly how many passengers were aboard or who they all were. The only passenger list was aboard the vessel. As a result of this tragedy, ships would thereafter leave a passenger manifest ashore. It is estimated that 190 died that evening, passengers and crew. But if the passengers cannot all be positively identified, what of the crew?

This article is an attempt to discover information about the men and women who made up the crew of the Portland using records in the National Archives and Records Administration–Northeast Region (Boston). The first place to look would be the customs records of Portland, Maine, the steamer's home port. Unfortunately, many 19th-century records are incomplete, and there are few records in the Archives for this port. For the Portland, there are no crew lists, shipping articles, manifests, or vessel documentation.

There are records related to the Portland in the Life Saving Service station logs along the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. These provide information on the aftermath of the storm, noting the bodies and artifacts washed ashore. At the Cahoons Hollow station, on November 28, 1898, the body of George Graham, a Negro, washed ashore. He is identified by name in the log entry, and he is the only crew member whose body was identified at the time of recovery.

The case files of the U.S. District Court at Portland, Maine, contain the petition for limitation of liability filed by the Portland Steamship Company in response to the civil suits filed by the estates of deceased passengers. There is little information about the crew. Eventually the court ruled the sinking an act of God, thus absolving the company of all responsibility. The suits were withdrawn.

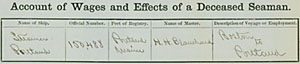

In the records of the U.S. Circuit Court, Maine, one finds the case files of deceased and deserted seamen, 1873–1911. Under an act of June 7, 1871, Congress authorized the office of "shipping commissioner" in federal circuit courts whose jurisdictions included seaports or customs ports of entry. Among their duties, commissioners collected the wages due to deceased seamen from the vessel's master or owners and turned the money over to the court for delivery to the legal heirs. Unclaimed monies would eventually be turned in to the U.S. Treasury. Claimed funds would be paid only after the court was satisfied that the proper person was getting the money. To that end, these case files provide extensive family information through preprinted forms or affidavits or both.

|

The wage papers filed with the circuit court can be a valuable source of genealogical information about lost seamen. This account documents wages owed to Arthur Johnson. |

The first is that of John C. Whitten, a watchman survived by a wife and four children. He was owed $35.00 for one month's wages. His widow, Lettie A., filed the claim on behalf of herself and her children, ages 6 to 12.

The 1900 U.S. population census shows Lettie, age 32, residing at the "Invalids Home" in Portland, Maine. I called the Maine Historical Society in Portland to learn what type of institution this was, and I was informed that this was a home "where self-supporting women could be cared for at a nominal price when by reason of overwork or illness they required the rest and nursing which could not be secured elsewhere." Of the four children, daughter Lettie, age 8, was placed as a "ward" with a private family; two of her brothers were at the Good Hill Farm, Fairfield, Maine; and the third son could not be located in the census. Further research into the Home records and Cumberland County Court records might reveal details on these events. One cannot but wonder if the dispersal of the family came about as a result of the husband's death in 1898.

Where crew lists exist, it is an easy matter to identify race and origin. In cases such as the Portland,census records can reveal that information. African Americans served as crew on many of the coastal steamers in the 19th century. From the 1900 U.S. census and the 1901 provincial censuses of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, I learned that several members of the crew, besides George Graham, were black, and that many had been born in Canada.

For Ellen Johnston of Portland, Maine, the sinking of the vessel was doubly tragic. Both her husband, Arthur, and her sister, Mrs. Carrie E.M. Harris, were lost. Ellen filed a claim for her husband's wages on December 19, 1898. She stated that her husband had been born at Moose River, Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, on April 2, 1848. His parents were both deceased, and his survivors included three children, Archibald, Harriet, and Josephine. The 1900 census of Portland, Maine, showed Helen [sic] with her children and revealed that they were black, all born in Nova Scotia.

On that same day, Ellen also filed a claim for the wages of her sister. From this we learn that Carrie was born at St. Marys Bay, Nova Scotia, November 10, 1840, to David and Cellia [sic] Sibley, both deceased. She was a widow and had no children. Her siblings included one brother, John Sibley, and two sisters, Cellia Sibley, and Ellen Johnson [sic]. In January of 1899, both John and Cellia Sibley sent affidavits from Nova Scotia to the court in Portland, asking that their share of Carrie's wages be paid to their sister, Ellen Johnston.

Carrie Harris's sister Cellia Sibley sent the circuit court her consent for Ellen Johnston to receive the balance of Carrie's wages.

When the Portland went down on November 27, 1898, the records on board went down with her. But by using other sources, particularly the 1900 U.S. federal census and the 1901 Canadian census as well as the records of deceased and deserted seamen of the U.S. Circuit Court in Maine, researchers can reconstruct information about the crew. The records give not only the names of the crew but can flesh out their lives as well.

Click here for the Final Crew List of the Steamer Portland.

Saturday, August 21, 2010

Joshua James ~ A Celebrated Lifesaver

"Here and there may be found men in all walks of life who neither wonder or care how much or how little the world thinks of them. They pursue life's pathway, doing their appointed tasks without ostentation, loving their work for the work's sake, content to live and do in the present rather than look for the uncertain rewards of the future. To them notoriety, distinction, or even fame, acts neither as a spur nor a check to endeavor, yet they are really among the foremost of those who do the world's work. Joshue James was one of these."

~~Sumner Kimball, Superintendent of the U.S. Life-Saving Service

~~Sumner Kimball, Superintendent of the U.S. Life-Saving Service

Joshua James was born 22 Nov 1826 in Hull, Plymouth, MA and died there 19 Mar 1902. He was the ninth of twelve children born to William James and Esther Dill, both of Holland.

He was called a "great caretaker" by his siblings and was reared by his sister, Catherine, after their mother and baby sister drowned in the sinking of the Hepzibah on 3 Apr 1837. Returning from Boston through Hull Gut, the sloop, which belonged to Joshua's older brother Ranier, was engulfed by a sudden squall and thrown on her beam ends by a flat of wind. She filled with water and sank before Mrs. James and her baby daughter, who were trapped below in a cabin, could be rescued.

This event had an important influence in shaping Joshua's career as a lifesaver. "Ever after that," said his sister, "he seemed to be scanning the sea in quest of imperiled lives."

A natural seaman, Joshua started going to sea early in life with his father and brothers. On one occasion, while he was sailing a yacht in dense fog, all bearings apparently lost, someone asked him where they were. He replied, "We are just off Long Island head." "How can you tell that?" he was asked. "I can hear the land talk," he replied.

In 1958, Joshua married Louisa F. Luchie, daughter of the John Luchie and Eliza Lovell. Louisa was born June 1842 in MA. At the age of 14, she had saved the life of a swimming companion, establishing a tradition of lifesaving that ran through their families. "Little Louisa" was Joshua's fourth cousin. When a writer expressed some surmise at the disparity in their ages, Louisa naively explained that Joshua had always had his eye on her and had waited for her to grow up. Louisa possessed unusual beauty of face and figure, as well as a rare sweetness of disposition and marked intelligence. They were a well-matched couple, as Joshua was an exceptionally handsome, well-built man with a genial face and good humor.

Joshua's lifesaving career began in 1842, when he joined the Massachusetts Humane Society in the rescue of the Harding's Ledge. He went on to become famous as the commander of civilian life-saving crews in the 19th century and was involved in a number of rescues over the years ... so many that a special silver medal was struck for him by the Humane Society in 1886 "for brave and faithful service for more than 40 years." The report said, "During this time, he assisted in saving over 100 lives.

- He was awarded a bronze medal on 1 Apr 1850 for the rescue of the crew of the Delaware on Toddy Rocks.

- In 1864 he helped rescue the crew of the Swordfish.

- In 1871 he helped in the rescue of a schooner.

- In 1873 he helped in the rescue of the crew of the Helene.

- In 1876 he was appointed keeper of four Massachusetts Humane Society lifeboats at Stony Beach, Port Allerton and Nantasket Beach.

- On 1 Feb 1882 he and his crew of volunteers launched a boat in a heavy gale and thick snowstorm to rescue the crew of the Bucephalus. On the same day, they rescued the crew of the Nelly Walker.

- An exciting rescue was that of the crew of the Anita Owen on 1 Dec 1885. It was midnight and dark, with a northeast gale blowing a thick snow. Joshua and his crew got to a wrecked vessel under hazardous conditions and found 10 people on board. They could only take 5 at a time. The captain's wife was taken off first, then four others in the first load. On the trip to the beach, the boat was hit by a huge wave and filled, but everyone reached shore. The second trip was more dangerous: the steering oar was lost and wreckage was all about. They managed to get the remaining five crewmen ashore.

- On 9 Jan 1886, he and his crew rescued the captain of the Millie Trim, but were unable to save the rest of the crew.

- On 25 Dec 1886 he assisted in the rescue of 9 men from the schooner Gertrude Abbott via breeches buoy.

Breeches Buoy - The most famous rescue of his career, for which he received the Humane Society's gold medal, as well as the Gold Life-Saving Medal from the U.S. Government, took place on 25 and 26 Nov 1888 when he and his men saved 29 people from six vessels: among them the Cox and Green, Gertrude Abbot, Bertha F. Walker, H. C. Higginson, Mattie Eaton and Alice.

- On 27 November 1898, during The Portland Gale: he assisted in the rescue of two survivors from two vessels dashed upon Toddy Rocks; rescued 7 men via breeches buoy from a 3-masted schooner; opened the station to a family whose home was threatened by the storm; assisted in the rescue of 5 men from a beached barge; assisted in the rescue of three men from an unnamed schooner; and assisted in the rescue of three men from Black Rock.

Joshua died at the age of 75 while on duty with the U.S. Life-Saving Service and was honored with the highest medals of the Humane Society, the United States and many other organizations. He was buried with a lifeboat for a coffin; a second lifeboat made of flowers was placed on his grave. His tombstone shows the Massachusetts Humane Society seal and bears the inscription, "Greater love hath no man than this -- that a man lay down his life for his friends."

He is honored every year at his gravesite on May 23rd (Joshua James Day) by the Hull Life-Saving Museum and Point Allerton Station. His home, which was built in 1650, still stands and houses the Hull Life-Saving Museum. In 2003 the Coast Guard created the Joshua James award to honor the Coast Guard personnel with the most seniority in rescue work and the highest record of achievement.

Joshua and & Louisa had 10 children. Three daughters and 1 son died in infancy:

- Osceola F. James was born in MA Nov 1865. He became a sailor and master of the Myles Standish. As captain of the Hull volunteer life-savers, Osceola received a gold lifesaving medal and a record approaching his father's.

- Bertha Coleta James was born in MA Mar 1870.

- Rosella Francesca James was born in MA Mar 1873.

- Genevieve Endola James was born in MA Oct 1879.

- Edith Gertrude James

- Louisa Julette James

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)